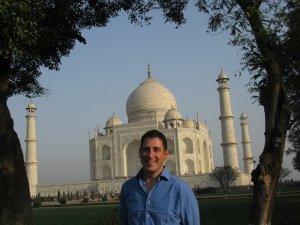

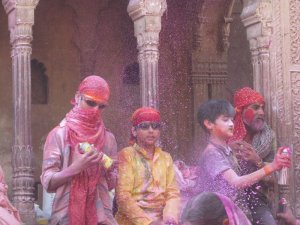

In the last week, my travels have taken me to two of the great mosques in India (Agra and Fatehpur Sikri), to “play” in the Hindu festival Holi, to the Sikh Golden Temple, and finally to Dharamsala, home to the Tibetan Buddhist leader Dalai Lama and his government-in-exile. It’s enough to confuse even the most committed agnostic.

The Golden Temple was particularly stunning, meriting three separate visits, including one at 4am. The sight of thousands of circumambulating pilgrims combined with the sound of the recitation of the Sikh holy book the Adi Granth (read continuously 24/7/365) was unforgettable.

The Golden Temple was particularly stunning, meriting three separate visits, including one at 4am. The sight of thousands of circumambulating pilgrims combined with the sound of the recitation of the Sikh holy book the Adi Granth (read continuously 24/7/365) was unforgettable.

Amidst this spiritual sensory overload, I took a trip over to the India-Pakistan border on Sunday, for a bizarre display that highlights the contrasting fortunes of these two countries. On this most arbitrary of borderlines (drawn on the map in 1947), the “lowering of the flags” at Wagah has become something of an attraction for patriotic Indians and intrigued foreigners alike.

Driving out through the super-organised Punjabi fields (this area is the breadbasket for the country and has a prosperous feel to match) I noticed an advert painted on a building wall – “BHATIA GUN HOUSE Licensed for pistols and Gun Cartridges”. I wondered briefly if Wagah might have a touch of the Waco about it. In the event, it was all pretty good-natured.

I arrived at the border at 5.30, walking the last kilometre with thousands of others for the prequel to the sunset ceremony.

On the Indian side, in a large, incongruous stadium-style hemisphere of concrete seating, a few thousand colourful over-excited spectators were being whipped into a frenzy by a scary-looking ringleader in dark glasses. The screams – of “HIN-DU-STAN!” and “VAN-DE MA-TA-RAM!” (Hail to the Motherland) – were deafening. One of my neighbours was quick to assure me that everyone loves everyone really.

On the Indian side, in a large, incongruous stadium-style hemisphere of concrete seating, a few thousand colourful over-excited spectators were being whipped into a frenzy by a scary-looking ringleader in dark glasses. The screams – of “HIN-DU-STAN!” and “VAN-DE MA-TA-RAM!” (Hail to the Motherland) – were deafening. One of my neighbours was quick to assure me that everyone loves everyone really.

The view on the Pakistan side might be a bit different. The contrast with the happy-go-lucky growing-at-5%-a-year Indians was stark. The Pakistani side looked dismal. A paltry couple of hundred sat in a similar sized amphitheatre. This lot looked dour, sad, dressed in bland greys and blacks, the women in burkhas against tatty white-washed seating. It was all a bit sad.

The view on the Pakistan side might be a bit different. The contrast with the happy-go-lucky growing-at-5%-a-year Indians was stark. The Pakistani side looked dismal. A paltry couple of hundred sat in a similar sized amphitheatre. This lot looked dour, sad, dressed in bland greys and blacks, the women in burkhas against tatty white-washed seating. It was all a bit sad.

The ceremony itself – choreographed in advance by both sides and involving copious chest-puffing and goose-stepping – was greeted with whoops, cheers, and more flag-waving and foot-stomping than a crucial Celtic-Rangers head-to-head.

It was a vivid reminder of the continued blurring of the lines between politics, the military, warfare and sport – and of the strange relationship between two countries created out of the back-end of a failing imperial adventure in 1947.

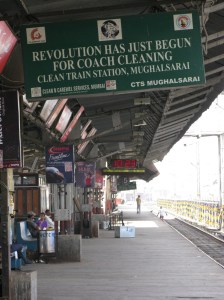

A new Lingua India?

There’s something interesting going on within India itself too. Despite apparent frequent displays of pan-national pride like the one above, regionalism is definitely rearing its head for the April/May elections. I noted the huge diversity of languages across India in an earlier post, that diversity is now being reflected by a rise in the power of locally attractive politicians. You might even see one of them – Mayawati, a powerful Dalit women who looks like she could pack a punch – becoming a critical power-broker when the time comes to appoint a PM…

A common language is, in many ways, the glue that keeps a country together. So it is interesting to note that English is giving Hindi a run for its money. Consider these facts:

1. If a North Indian from Delhi wants to communicate with a South Indian from Kerala or Tamil Nadu, he will most likely do so in English. (If he tries Hindi, he will probably get a blank look from the Southerners, whose own languages of Malayalam and Tamil are worn as a badge of honour)

2. The huge adverts for private schools everywhere always say “English medium” or “Hindi medium”. If the relative number of each is a reflection of market demand, India wants its children speaking English first and foremost. .

3. At the showing of Smile Pinki that I attended in Varanasi, everything (except the film) was conducted in… English. And that despite the fact that the audience was (with the exception of me and one other) entirely Indian.

It’s all rather interesting. After a long period after partition where English was lingua non grata (while Hindi was being pushed forward), market forces may be shifting things. Most people here are also clear that English gives India something of a business advantage over its arch-rival China.

Meanwhile the way English is used by Indians continues to be as flowery as ever. Reading the cricket reports in the Times of India or the Indian Express (both English language) is sometimes like reading McGonagall at his worst. This from the Times of India after they lost a couple of games in New Zealand (the emphasis is mine):

“The Indian cricket team is like a sleeping ocean, or a dormant volcano, if you please: One just doesn’t know when it will wake up and take the shape of an all-consuming storm or erupt into a flame-throwing monster. New Zealand heard the first roll of thunder, saw flashes of lightening too, on Tuesday afternoon; they also felt the earth growl from deep within as India’s batting all but exploded in unison. They are clearly worried, if not scared.”

The article goes on to talk of fighting “ripple-to-ripple, wave-to-wave”, of “follow-up Tsunamis”, of “getting past other brooks, creeks, and even seas”. There’s nothing like taking an analogy too far. Read the whole, wonderful, article here.

—–

Despite the attractions of feeling cold rain on my face for the first time in 4 months (Mcleod Ganj a.k.a Dharamsala is at 2827m), I am moving southwards from Dharamsala tonight so that I can get East before my visa runs out.

Toodle pip!