Beauty in Perfection – The Taj

The Taj Mahal is such a cliché these days that everyone worries that it won’t live up to the hype.

I and two friends arrived in Agra determined to avoid this. We employed two tactics – first, we crept up on it, visiting the Red Fort to get a the view down the river Yamuna on the first day. Secondly, we arrived during the full moon phase, getting the opportunity to view it by near-full moonlight the night before we visited. Both hinted at what was to come.

The day of the main visit arrived. We arrived at the gates at the recommended ungodly hour.

We immediately found ourselves under fire from a series of would-be guides. Rather than prolong the agony, we selected one partly on the basis that he bore more than a passing resemblance to an Indian version of Oddjob. But when his first sentence in English turned out to be utterly incomprehensible, I had to cut him short. He waddled off, clearly crestfallen, but returned in double-quick time with another man.

I looked our replacement up and down. If you can judge a man by the crease in his trousers, then this guy was top-notch. He was 70, a former schoolteacher with excellent English and a proud, upright bearing. We agreed terms. As he set off at a crisp pace into the main area, I thought it polite to enquire as to his name. Without breaking step he responded “Master!” It was clear who was in charge on this tour.

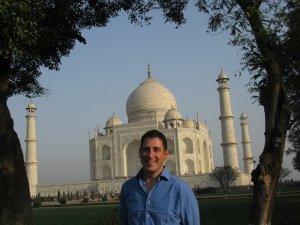

“Master” and the other guides are convinced (often rightly) that people only really come to the Taj for the photos. They therefore make it their business to know every spot for a “classic shot” on the walk through the garden to the main Mausoleum. Every 50 yards or so, Master would pause, and issue the stern command “Come! Camera! Please!” We were expected to drop everything, give him our cameras, assume the position, and get snapped, while he issued firm commands such as “Back!”, “Please! Come this side!” and “Smile!”

Unfortunately the speed with which he dispatched each photo meant that many of these rendered the Taj’s beautiful symmetry at rather Dutch angles. They are rather wonderful.

Unfortunately the speed with which he dispatched each photo meant that many of these rendered the Taj’s beautiful symmetry at rather Dutch angles. They are rather wonderful.

As we walked on, his impeccable explanations of the history and the 22-year construction came into their own. His love for this astonishing building came shining through. The beauty of the Taj lies in the minutest detail of an inlaid piece of jade or agate just as much as in the whole building seen from afar. It is a truly gestalt experience.

Three hours with Master at the helm passed in no time at all as he hustled us through back doors and shared his tales gleefully with us.

As we finished the tour, he finally let his guard down, revealing his true name – Shamsad Uddin. Shamsad sheepishly produced a couple of crumpled photos. The first was of him guiding India’s most senior general, the second of him guiding Lalu Prasad Yadav (see previous post).

We had clearly drawn the long straw – it had been our lucky day.

Beauty in Chaos – “very too much Holi!”

I had a taster of the Holi Festival while in Udaipur. As it turned out, that was not even worthy of being called a taster.

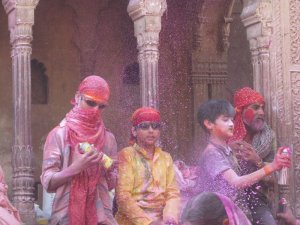

Minor celebrations go on for a month, but everything culminates in the main event held on the night of the Full Moon and the following day, when vaste swathes of India become madness personified and throw coloured dye, powder, and sometimes even paints at each other.

As the festival is associated strongly with the Hindu deity Krishna, we decided to head to Vrindavan (near Agra) where he supposedly grew up for the main event. Our rickshaw driver was clear – “Vrindavan is very too much Holi!”

We prepared to leave Agra. Our friendly Punjabi hotel owner warned ominously of ruined cloths and less pleasant substances being flung with abandon in impoverished Vrindavan. I therefore decided to try and blend in, buying a white Kurta Pyjama. Which did nothing of the sort.

We prepared to leave Agra. Our friendly Punjabi hotel owner warned ominously of ruined cloths and less pleasant substances being flung with abandon in impoverished Vrindavan. I therefore decided to try and blend in, buying a white Kurta Pyjama. Which did nothing of the sort.

Remarkably, my new attire stayed near spotless as we hurtled precariously in a rickshaw up towards our destination, huge bonfires on the roads illuminating our path.

Morning came, and I headed for the Pujah (morning worship) in the Krishna temple to get a sense as to what this was all about. For us Brits, the “Hare Krishna mob” tends to mean the shaven-headed tambourine-banging crowd on Oxford Street or Princes Street. There were a few of those in the temple, but they were vastly outnumbered by Indians demonstrating a level of devotion and love in worship that is amazing to observe and hard to describe.

By 7.30am, it was time to head onto the streets. The madness began. After half an hour we were all covered and had been well and truly “holi’d”. Unfortunately, wandering hands were sadly in abundance and the girls had to head back. I continued to explore alone – for which pictures speak louder than words.

We returned to Agra by train, feeling not the least out of place in dye-spattered clothing. It had been an amazing 24 hours, encompassing two spectacular experiences – one of architectural perfection, one of colourful chaos.

An overnight train last night, and I’m now in Amritsar on the edge of Punjab province by the Pakistani border. More in due course.

[P.S. They say it is good luck when a bird defecates on you. Certainly, since the first incident on my first day in India (Bombay street corner), things have gone pretty well.

The second incident happened exactly 120 days later, in slightly more pleasant surroundings, while gazing at the Taj Mahal. Perhaps the Gods felt I needed an update. Or a reminder.]