“Indian Railways” is, by any account, a remarkable organization. Various sources claim that:

a) it is either the largest or second largest (after the Chinese Army) employer in the world

b) the network carries the equivalent of the population of Australia every day

c) it has one of the most complex revenue collection systems in the world

The daily reality is equally astonishing.

We arrived at Mughal Sarai station (just outside Varanasi) at 8.30am, greeted by a cow who had clearly got bored of queueing up for the ever-chaotic Enquiry Office. Although it would be unfair to say this is a frequent sight, you get so used to randomness here that it took a second to register just what a strange picture this was.

Leaving Ermentrude behind, we walked through the upright scanner that most Indian stations now have for these security-conscious times. The operation of these is just as random as the queue for enquiries however – the sound of the beeper alarm is no guarantee that you will be stopped, and if your bag is too big to squeeze through these flimsy structures, doing a quick side-step round the side is usually tolerated by generally bored looking officials.

The train was delayed. I was quite happy to draw on my ever-increasing well of patience. I decided to have a look around.

A couple of young official-looking boys with flimsy fluorescent yellow waistcoats (so loved by officials the world over) walked past. They came over. The usual pleasantries were exchanged, involving interrogation as to our country of origin (more on that in another post). It turned out that they were riding on the trains in a joint WHO/Rotary International programme, administering polio drops to children under five. Given the Australia statistic above, this seemed like a deeply practical initiative.

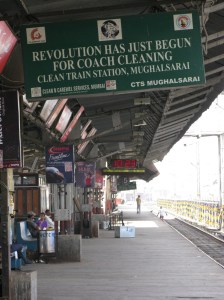

As the boys walked off to continue their walk, I looked up the platform. There was something wrong. The platform was not just clean, it was close to spotless. I looked up to see a sign:

“REVOLUTION HAS JUST BEGUN FOR COACH CLEANING

Clean n Carewel Services CTS MUGHAL SARAI”

It seemed remarkable. As the Western world privatizes its banking system, could private contracts for railway station maintenance really be establishing a foothold in India?

It seemed remarkable. As the Western world privatizes its banking system, could private contracts for railway station maintenance really be establishing a foothold in India?

The train arrived, a mere 90 minutes late, which is actually not bad for a train that had been on the tracks for 10 hours and had at least another 12 to go. (We were joining the Sealdah-Jaipur Express, which cuts a swathe through the Gangetic Plain from Bengal to Rajasthan – click here for route).

Within a few kilometres we were headed into the interminable expanses of countryside, so uniform across the entire country that, as John Keay points out in his History of India, “the traveller – even the Indian traveller – may have difficulty in identifying his whereabouts”.

Despite this uniformity, there is always endless fascination and plenty of food for thought. Within a single minute you pass seemingly random piles of concrete pillars (actually railway sleepers); village settlements with haystacks and flimsy homes with roofs made from plastic sacks; railway crossings with a surprisingly large number of assorted cars, cycles, rickshaws, pigs, cows, monkeys, and foot passengers waiting patiently to cross; a concrete town settlement looking strangely cubist with it’s concrete box housing; school children immaculately dressed on their way to their lessons.

But these are interruptions to the hours spent staring out of the windows at vast tracts of cultivated land as the train trundles on. (It was in Karnataka when the full scale of what these tracts mean first dawned on me – with little to no mechanization in many parts of the country, the crops still have to be harvested. By hand).

We pulled into Allahabad station, where the Ganges and the Yamuna rivers converge. Two men in smart green jump-suits climbed on – one walked purposely through the carriage spraying pungent air freshener everywhere, while another brought on what looked like a steam vacuum cleaner and started cleaning the floors. Someone, somewhere, had spotted the opportunity of these private cleaning contracts. “Clean n Carewel” were clearly a successful outfit.

The opportunity to chat to fellow passengers is one that I rarely turn down (even at the risk of occasionally being sucked into a vortex of interminable conversation). On this journey, my favourite was the Sikh who sniffily picked up the history I was reading, turned straight to the Index and announced loudly that it couldn’t be any good because it only had a dozen pages or so worth of references to Sikhs. I tried to point out that a) the book was 500 pages, b) it endeavoured to cover 5000 years, and c) Sikhism (though an essential part of the mix) hasn’t exactly dominated Indian society since its founding in the late 15th century. But he was not convinced.

We finally pulled into Agra Fort station in the evening, emerging back into the chaos of the streets from the relative tranquility of the journey.

There is a whiff of change in the Indian Railway system. It almost feels like things have even improved while I have been here (although admittedly the sample is rather low and restricted to passenger trains – 70% of Indian Railways revenue comes from shifting freight).

Lalu Prasad Yadav is the man in charge, a bruiser of a politician from the wrong side of the tracks, with a background that is colourful even by Indian political standards. It is he that is credited by some with making the difference, and in a tactic employed the world over in the run-up to elections, he is also promising massive investment.

He is a toughie, from the toughest of the tough lands in India, Bihar. But then as one of my fellow passengers said, the Biharis may be the only ones tough enough to keep up with the pace of change here.

I am in Agra and the surrounding area for a few days.